Shenanigans or Symbolism? On the Beasts in Count Oettingen’s Psalter

Recently, a truly magical manuscript came into our possession. It is a richly illuminated Psalter from South Germany, made for one influential aristocrat from the Oettingen family: Ludwig of Oettingen the Younger. As this blogpost will show, this richly decorated book of private devotion comes with some remarkable features.

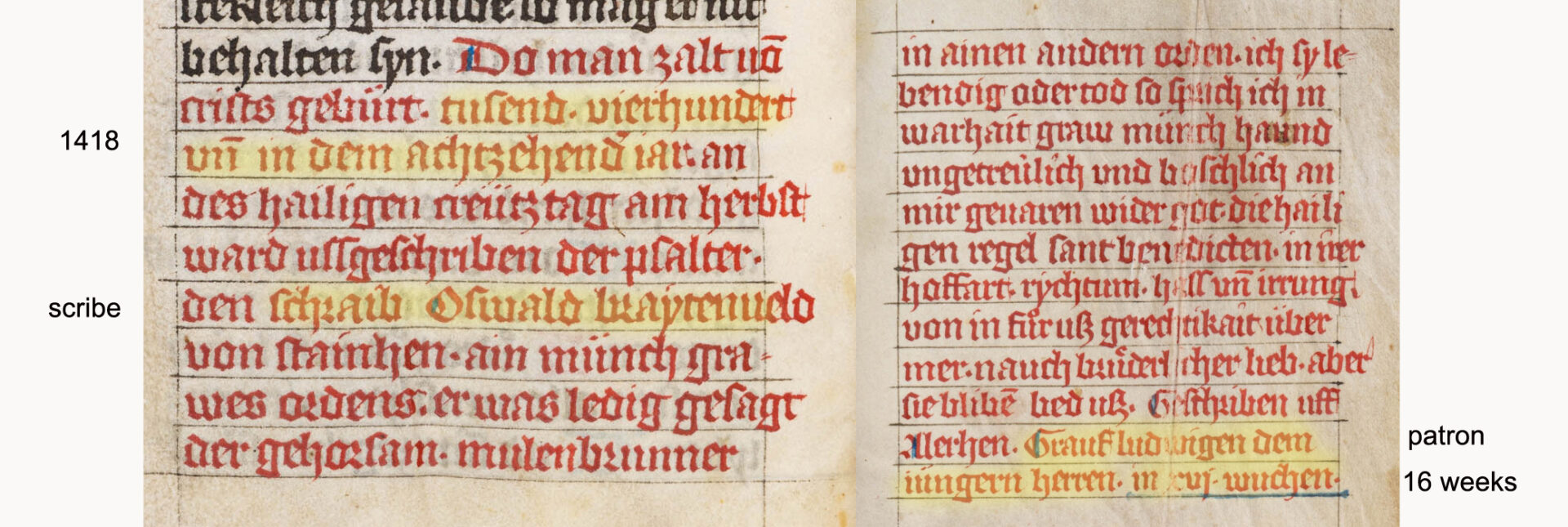

The scribe of the book gives us his name on the last page of the book. He was a Cistercian monk called Oswald Braytenveld, who came from Steinheim near Alerheim, a place in the Swabian Jura famous for its meteorite craters. It is not uncommon for scribes to sign their work, but Oswald even tells us for whom the manuscript was destined. He writes that he accomplished the Psalter for Count Ludwig the Younger of Oettingen.

Colophon on ff. 251v-252r: “This psalter was written down on Holy Cross Day in autumn (14 September) in the year one thousand four hundred and eighteen after the birth of Christ. The scribe was Oswald Braytenveld of Steinhein, a monk of the Grey Order (i.e. Cistercian). […] Written on All Saints’ Day (1 November). Count Ludwig the Younger in sixteen weeks.”

We even know the exact date on which he completed the book, as he states that he finished his work on 14 September 1418. Furthermore, he reveals the astonishing fact that it took him only sixteen weeks to complete this book. Would you have assumed such an incredible speed for an extensive work of 252 leaves?

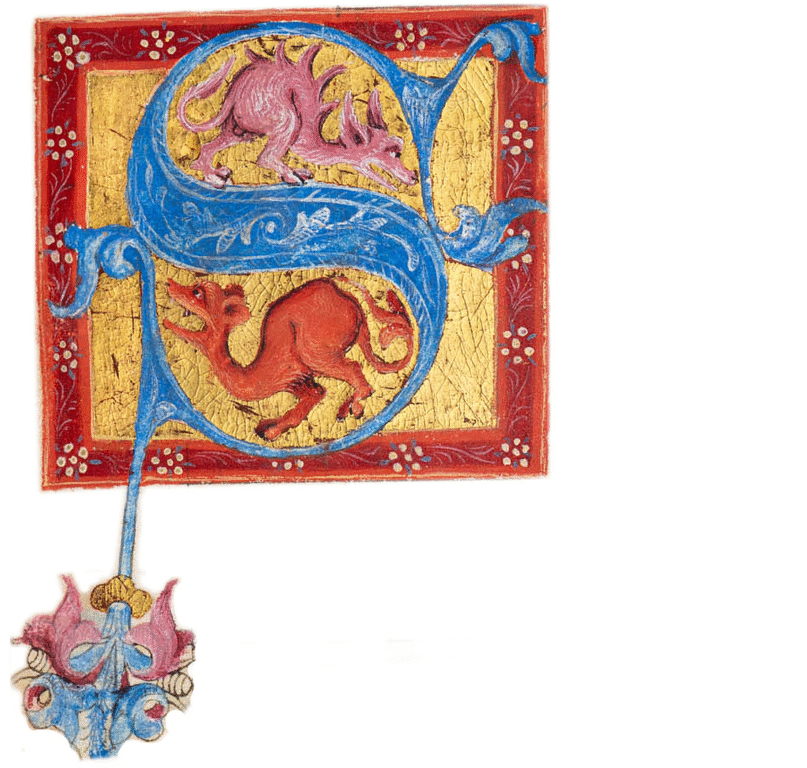

Another special feature of the Psalter are the numerous dragons that appear in the initials to introduce the psalms as well as in the margins of the leaves. Most of them do not look particularly frightening.

f.1r Initial S with two dragons

Those two have to hunch over considerably to fit into the letter S, and they don’t look too happy about it.

Who would have expected to find these magical creatures, normally associated with evil or Satan himself, in a private devotional book? The answer to this mystery lies in the book owner’s membership in an aristocratic chivalric order founded in 1408 (or maybe even a decade earlier) by Sigismund of Luxembourg, King of Hungary and later Holy Roman Emperor.

The insignia of the order consisted of a dragon strangled by its own tail, and for the high-ranking members crowned by a flaming cross.

Embroidered badge of the Order of the Dragon. Southern Germany, around 1430, Bavarian National Museum, Inv. T3792

This order called itself the Societas Draconistarum (Society of the Draconists) and declared its goal to defend Christianity against the Ottomans, pagans and heretics. Sigismund either founded the order on the occasion of his marriage to Barbara of Cilli in 1408 or he updated the order’s statutes in that year, which was actually done on several occasions. The historical sources provide conflicting information on this point.

Some even claim that the Order of the Dragon originated from a preceding order called the Order of St. George. And indeed, this saint as the slayer of the dragon occupies a very prominent place in a wonderful camaïeu bleu initiale at the beginning of Psalm 26.

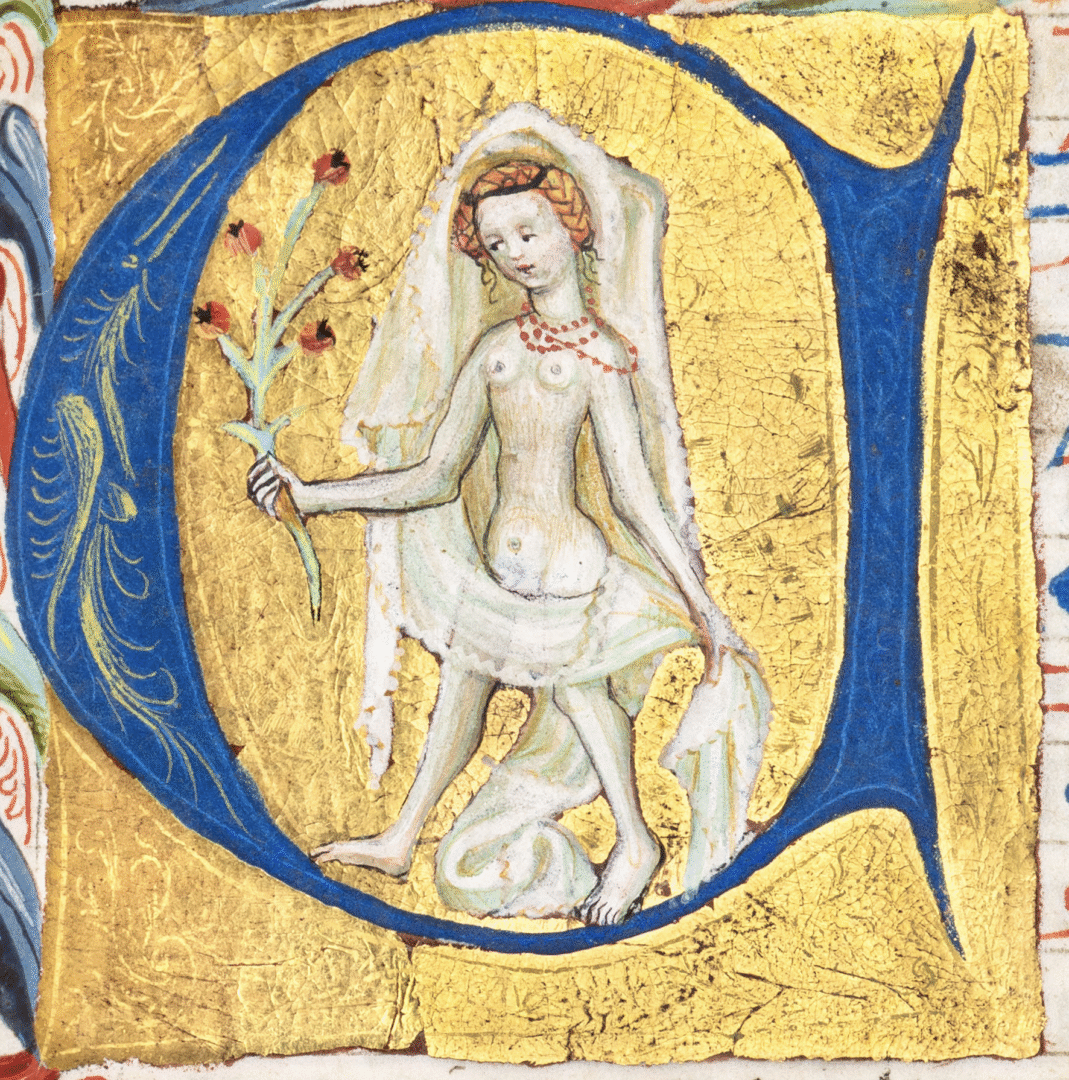

f. 32v St. George kills the dragon (Detail)

Although the history of the Order’s foundation is marked by some inconsistencies, the evidence suggests that the rules of the order were reformed several times during its existence. Among other things, the king changed the conditions regarding the nationality of members. Originally, the inner core of the order had twenty-four members of Hungarian origin. They got the full insignia of the order, which was a circular dragon with a flaming cross above it. One remarkable fact about this special order of knights should be highlighted here: it accepted women from the very beginning, and one of its founding members was the Queen of Hungary herself.

Since the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, the Kingdom of Hungary had been seriously threatened by the Ottomans. At the beginning of the 15th century, unrest in Bohemia and neighbouring countries, triggered by the reformers around Jan Hus and the followers of John Wycliffe, grew so strong that Sigismund urgently needed support from neighbouring countries. In order to win over these followers, they were also admitted to the Order of the Dragon. However, these non-Hungarian members only received the dragon (without the cross) as their insignia.

These circular dragon figures have a tradition dating back thousands of years, usually taking the form of a dragon biting its own tail. An example of this is the Ouroboros in ancient Egypt, which does not symbolise evil, but eternal return or the overcoming of evil.

In Ludwig von Oettingen’s Psalter, we find neither a dragon strangling itself with its tail nor one biting its tail. Instead, there are several with knots in their necks.

f. 234r Dragon with a knotted neck (Detail)

f. 12r Another dragon with a knot in its throat, stabbed by a vine (Detail)

Although none of the dragons in this manuscript imitate the circular emblem of the Order of the Dragon, we are nevertheless convinced that the dragons refer to Ludwig the Younger’s affiliation the Order. It is well documented that his father, Ludwig XI of Oettingen (known as “the Bearded”), was as Sigismund’s court master and hence a member of the Society of Dragons. The owner of our Psalter was also in the king’s service and certainly also admitted into the chivalric order. The imaginative dragons are undoubtedly a proud allusion to this membership. Moreover, 1418, the year in which our psalter was accomplished, times were extremely difficult for the Hungarian king. The unrest surrounding the reformer Jan Hus had been steadily growing, and a year later, in 1419, the first Defenestration of Prague marked the beginning of the Hussite Wars.

In these troubled times, Sigismund needed every ally he could get. The knights of his order had a duty to be loyal to the king and to defend the freedom of Hungary.

We have not yet found a satisfactory answer to the question of why Louis the Younger did not give any of his dragons the form of the defenceless monster that strangles itself. Perhaps the readers of this blog post have a theory. What is striking, however, is that the creatures in the borders tend to have a humorous or ironic quality.

Here we have a rather timid, pink dragon that look as if he is ashamed of his many teeth.

f. 22v Pink dragon (Detail)

These two look as if they have a hen or a rooster among their ancestors and don’t get along well with herons.

Dragons with cockscombs (Detail)

The above-mentioned ironic tendency is reinforced by the presence of monkeys, who are seen as imitators of human weaknesses and vanities and hold up a fool’s mirror to us with their pranks and jokes.

f. 102r Monkey with mirror (Detail)

f. 204r Monkey with weight around its neck, wearing a fancy jacket (Detail)

f. 214v A monkey tied up plays the mandolin (Detail)

The magnificent, tooth-baring otter on f. 66v probably has less symbolic meaning. It could perhaps be seen as a play on words between Öttingen/Otter, an allusion to the fearless family of Oettingen, who struck fear into the hearts of lions.

f. 66v Otter (Detail)

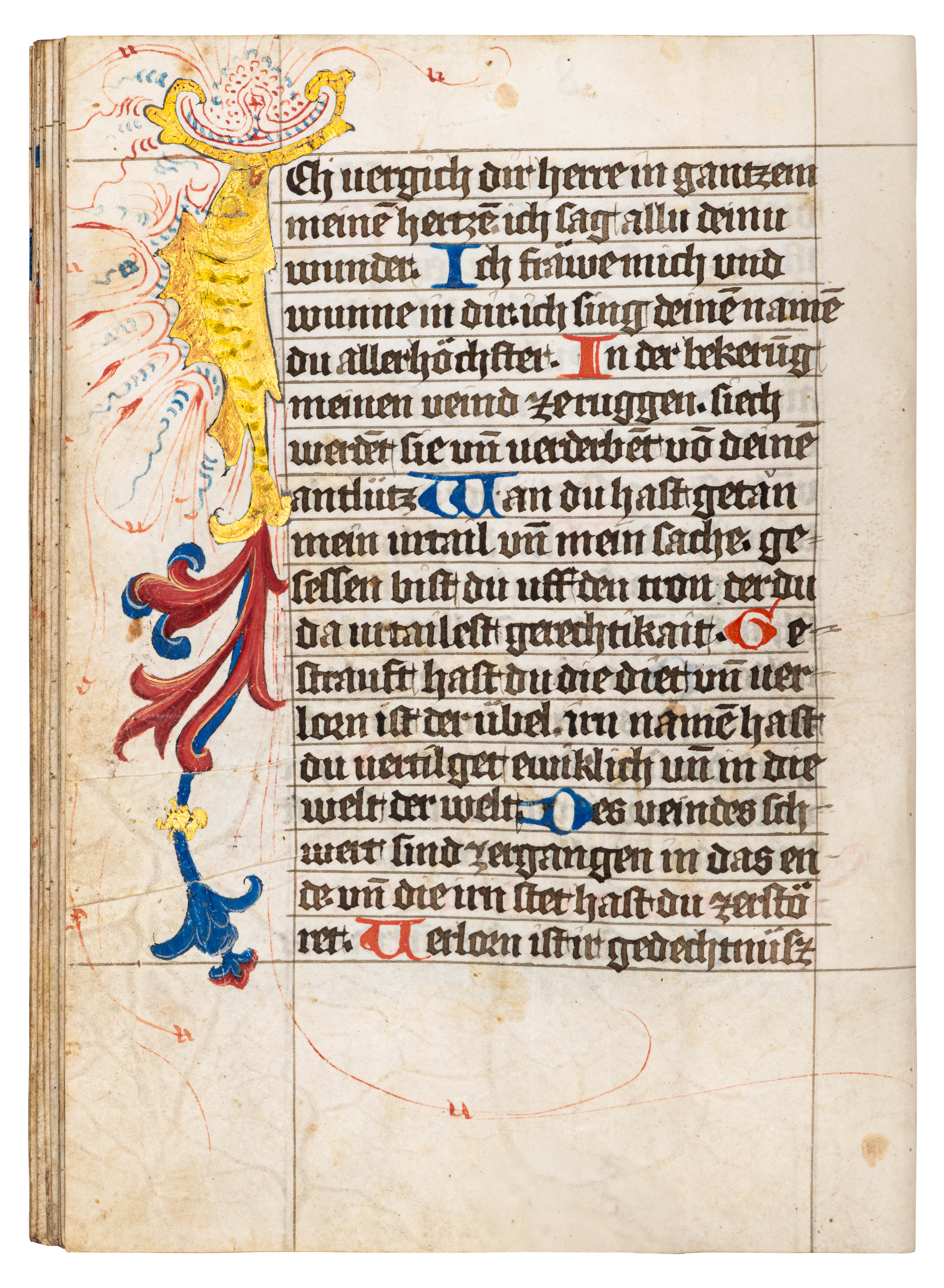

Golden fish often appear as a substitute for the letter I at the beginning of several psalms. The fish is a symbol of Christ, who once told his disciples: You shall be fishers of men.

f. 8v Psalm 9: “Ich vergich dir herre im gantzen meinem hertzen…”

Herons, one of which we already saw, had several symbolic meanings in the Middle Ages. They were also considered a symbol of Christ because they hunt eels and snakes and were therefore seen as conquerors of evil. They were also seen as a symbol of the knightly virtue of patience.

The goldfinch is also a symbol of Christ, his suffering and his resurrection.

f. 201v Goldfinch (Detail)

We are not totally sure what a dog biting happily into a vine symbolises. We do not think, however, it has any eschatological meaning.

f. 86v Dog (Detail)

Towards the end of our psalter, a duck waddles into the picture. In German, ‘Ente’ (duck) and “Ende” (end) sound almost the same. The illuminator has hidden three words in the pen flourishes that accompany the bird. We read ‘End für dich’ (end for you). Other interpretations by our readers are very welcome.

f. 245v “End für Dich” (Detail)