Bridging Time: The Journey of a Book of Hours Through Ice, Flood, and Dispersal

Karen Deslattes Winslow, PhD is offering fascinating insights into the challenge of reconstructing the trajectories and integrity of illuminated leaves from manuscripts that suffered harsh weather conditions.

The winter of 1407/1408 was severe across Europe. The rivers froze solid in France, allowing wagons and carts to traverse the ice. Then, as the Seine began to thaw in late January, flooding forced people along the banks to flee. Massive blocks of ice swept away three of the main bridges in Paris.

As Christopher de Hamel noted, it is astonishing that manuscripts were still being completed in these conditions, especially considering that many stalls, workshops, and ateliers dedicated to manuscript production were located on the Petit Pont, one of the bridges that had been destroyed. Yey, amidst this turmoil, manuscript production in the city continued.

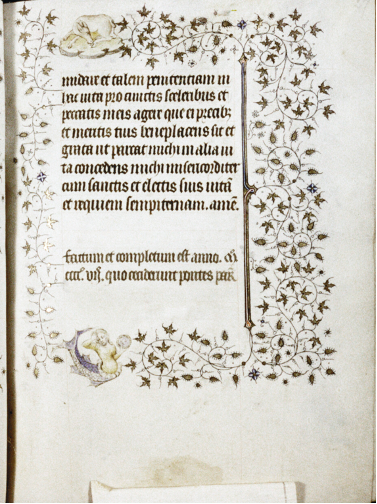

Two scribes reported the accomplishment in colophons in two separate Books of Hours: Oxford Bodleian Library MS Douce 144 and Chester Beatty Library WMS 103 (see figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Text page with colophon, 1408, Paris, Chester Beatty Library, WMS 103, fol. 158v.

Fig. 2 Text Page with colophon, 1407. Paris, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 144, fol. 27r.

Since 1834, MS Douce 144 has been safely stored intact in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. WMS 103 had a different fate and is now dispersed among several libraries and private owners.

Dr Jörn Günther Rare Books proudly presents a stunning leaf from this dispersed Book of Hours depicting St. Peter (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Mazarine Master, Saint Peter with the Key, Suffrages, once part of Chester Beatty Library Book of Hours WMS 103, 1408, Paris, Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books, fol. 162r.

The Book of Hours remained largely intact for over 400 years before a violent storm in 1846 set its current dispersed fate in motion. At that time, the book was in the collection of John Boykett Jarman, a London goldsmith and jeweller. According to Sir Frederic Madden, Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum, who heard the story firsthand, Jarman kept his manuscripts “secured” in tin boxes on the ground floor of his house. While Jarman was on holiday, a storm swept through London, causing the water to rise several feet in the room where Jarman kept his manuscripts.

The tin boxes sat in dirty water for three days. On his return, Jarman attempted to restore the damaged manuscripts by separating the leaves from their bindings and laying them flat to dry. He rebound the least damaged manuscripts and employed William Charles Wing to repaint several damaged illuminations.

Madden and Dr. Daniel Rock were invited to view the manuscripts in 1851. Madden recorded in his journal dated February 18, 1851 –

“The sight was really heart-rending! The loss is really frightful to think of! I wonder why Mr. Jarman did not hang himself at once!”

He also noted Rock’s comments – “nearly every leaf…blackened and the text almost wholly obliterated. Strange to say, however, the miniatures are by no means so injured and still retain their brilliance and delicacy of colouring.” This comment would certainly apply to the miniature of St. Peter.

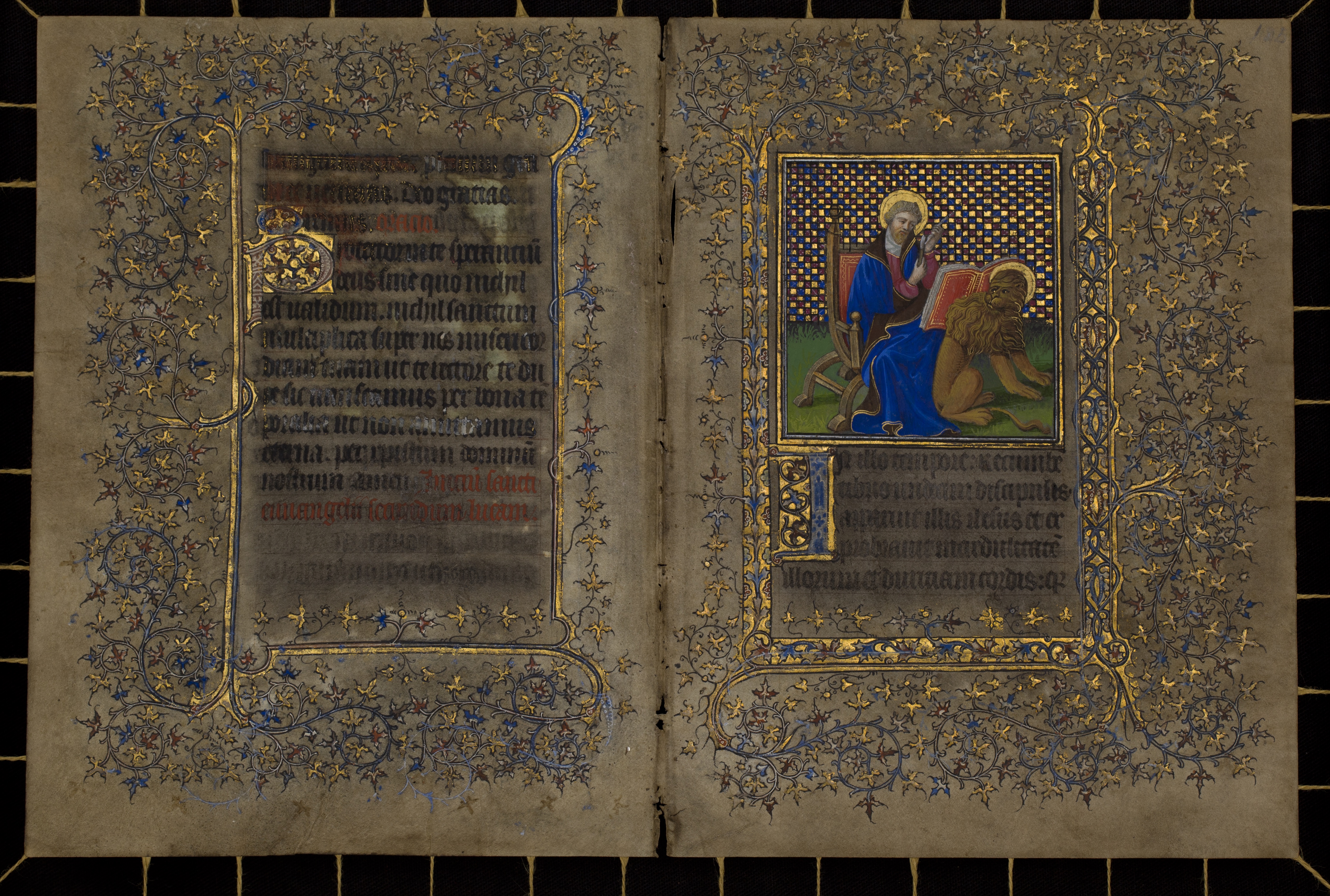

Jarman passed away on February 29, 1864, and four months later, his collection, including the Book of Hours, was auctioned at Sotheby’s: Lot 47# included the following description: “28 Miniatures in the best style of early French Illumination, but has suffered from damp.” The water damage was described as limited to the book’s beginning and end, including the Gospel Lessons that were misbound and placed in the back of the Book of Hours (see example of more damaged leaf, fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Mazarine Master, Saint Mark with Lion, Gospel Sequence, once part of Chester Beatty Library, WMS 103, 1408, Paris, Melbourne Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne, UniM Bail SpC/RB61AA.

On June 13, 1864, Edward Arnold of Dorking, Surrey, was the winning bidder. Upon Arnold’s death in 1911, the book passed down to his son, Andrew W. Arnold. In May 1929, Arnold put his father’s library up for auction, where the 1408 Book of Hours with its twenty-eight large miniatures was described as “A beautifully executed manuscript, unfortunately in bad condition.”

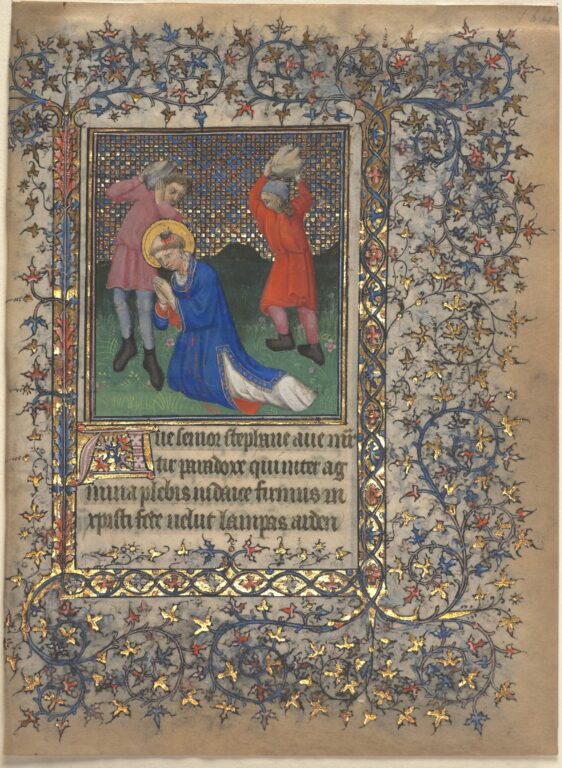

The American-born, but London-based collector, Alfred Chester Beatty, purchased the Book of Hours from the antiquarian bookseller Chaundry of Oxford and catalogued the manuscript as WMS 103. The damage to the manuscript probably prompted Beatty to break it up. In 1931, Beatty gave five leaves from WMS 103 to Harold K. Hochschild, including pages with miniatures of The Trinity, The Martyrdom of St. Stephen and St. Katherine (see fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Mazarine Master, The Martyrdom of St. Stephen, Suffrages, once part of Chester Beatty Library WMS 103, 1408, Paris, Princeton University Art Museum, Y1979 39-43, fol. 164r.

Fig. 6 Mazarine Master, Presentation in the Temple, Hours of the Virgin, 1408, Paris, Chester Beatty Library, WMS 103, fol. 48v.

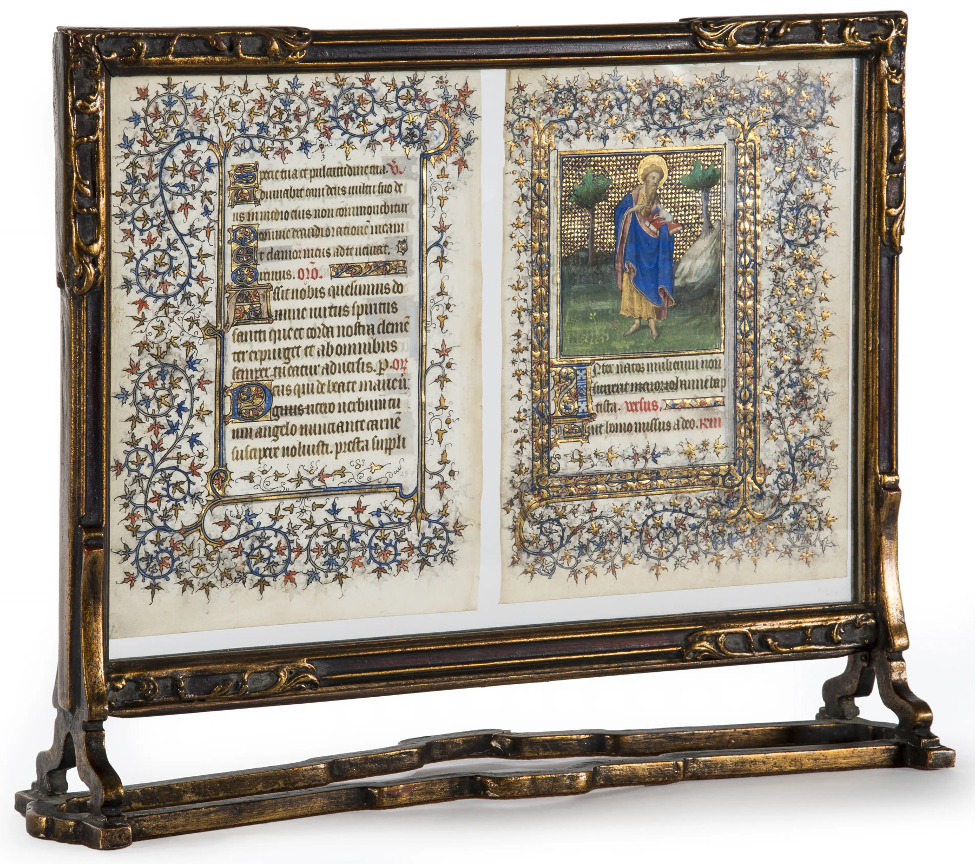

In 1932, Beatty shifted his focus to Islamic manuscripts and quietly listed six leaves with miniatures from WMS 103 at Sotheby’s under “the property of a gentleman.” These miniatures included the Angels and Shepherds, the Adoration of the Magi, the Presentation in the Temple, the Office of the Dead, St. John the Baptist and St. Paul (see fig. 6).

After Beatty’s death in 1968, what remained of WMS 103 was offered by Sotheby’s in 1969. The book was listed as Lot 58, and lots 58a through 58k were eleven miniatures Beatty had cut from the book and mounted between thin sheets of glass. Four were mounted with text leaves randomly selected from sections of the manuscript (see fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Catalogue description: “326 MINIATURE. Another leaf from the same Manuscript with Miniature of St. John the Baptist (68 mm by 62 mm) with border, diaper background, mounted on leaf from the same M.S. VERY FINE, in a similar frame. [1408], 22 March 1932 Sotheby’s Manuscript sale (Second Day, page 52 of catalogue)”.

The main manuscript contained eight miniatures, indicating Beatty likely removed only the best-preserved illuminations. Notably, the miniature of St. Peter was removed and mounted alongside folio 66, a text leaf from the Penitential Psalms.

Realising the significance of this manuscript for understanding the chronology of the French masters and the evolution of Parisian Illumination, in 2010 and 2011, the Chester Beatty Library re-acquired three miniatures (The Virgin and Child with Angels in a Garden, St. Michael Trampling on (or Vanquishing) the Devil, and The Presentation in the Temple) and the colophon with the 1408 reference.

The calendar, which recently reappeared at auction, records the feast days for St. Tugdual or Tudwal, Bishop of Tréguier, and St. Corentinus, Bishop of Quimper, supporting the hypothesis that the Book of Hours was commissioned as a gift for a member of the nobility in Brittany. Research by Gregory T. Clark on the Spitz Master Book of Hours uncovered masculine forms of Latin, suggesting the book was created for a male patron. A similar conclusion can be drawn for this Book of Hours, which features seven male saints (St. John the Baptist, St. Michael, St. Peter, St. Paul, St. Stephen, St. Martin, and St. Nicholas) alongside only two female saints (St. Catherine and St. Mary Magdalen) in the Suffrages.

Artistic Collaboration and Unique Features

In 2016, I attempted to trace and digitally reassemble the leaves of this manuscript. Analysis of the digitally reassembled Book of Hours reveals a homogeneity and cohesiveness only achieved by specialists working nearby. Examination of several leaves held in private institutions shows a high level of craftsmanship; despite the water damage, the leaves appear smooth and creamy, with no detectable gashes, insect holes, or patches.

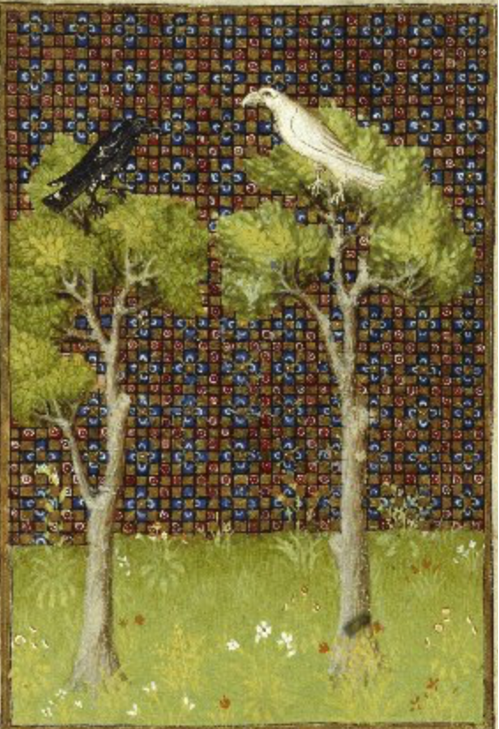

Let’s look closer at the miniature on the leaf we have in our gallery (see detail of St. Peter, fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Mazarine Master, Saint Peter with the Key, Suffrages, 1408. Paris, once part of Chester Beatty Library WMS 103, Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books, fol. 162r., detail.

St. Peter is depicted with a halo, seated majestically on a throne. He wears a tunica alba (white tunic) adorned with pleats at the waist and wide sleeves. Draped over his alba is a pinkish patterned stole that crosses elegantly over his chest. An ultramarine mantle, lined in red and secured with a gold clasp, envelops him. His short beard, a distinguished salt and pepper blend, complements his warm, ruddy complexion. He holds the key to heaven in his right hand, while his left hand gently supports the Gospels or his epistles resting on his lap. His gaze is intently fixed on the key, embodying his role as the vigilant gatekeeper of heaven.

In a 1952 inventory of Chester Beatty’s Books of Hours, the illuminator of this partially disassembled manuscript was initially identified as the Boucicaut Master. This anonymous manuscript illuminator was active in early 15th-century Paris and is celebrated for his vibrant colours, lush landscapes, ornate architectural elements, and the delicate facial expressions in his miniatures. He derives his name from Jean de Boucicaut, a prominent knight and patron of the arts recognised for his significant contributions to the illumination of Books of Hours and other devotional texts (see fig. 9).

Fig. 9 Boucicaut Master, The Annunciation to the Shepherds, Terce, Book of Hours, 1415-1420, Paris, Getty Museum, Ms. 22 (86.ML.571), fol. 67, detail.

In 1999, after Gabriele Bartz’s seminal publication Der Boucicaut-Meister: Ein unbekanntes Stundenbuch, the manuscript was reattributed to the Mazarine Master, named after one of his most notable works, a Book of Hours (Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine, MS 469), commissioned for Charles VI.

The Mazarine Master is recognised for his distinctive colour palette, which includes a rare lime green and a soft rose, both evident in this Book of Hours and a keen interest in drapery and the intricate rendering of folds. In contrast, the Boucicaut Master emphasises realism and perspective. Whereas, the Mazarine Master’s creations tend to exhibit a flatter, more decorative quality in their figures (see fig. 10).

Fig.10 Mazarine Master, The Annunciation to the Shepherds, Terce, Book of Hours, 1410-1420, Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine, Ms 469 f. 056v, detail.

Ultimately, the production of this manuscript was likely a collaborative effort rather than the work of a single master, involving loosely affiliated illuminators trained to work in a typical style using similar models and pattern books. The same skilled scribes and artists who crafted opulent manuscripts for kings and queens also collaborated with lesser-known noble patrons.

While suppression of individuality was the standard for transcribing text, freedom of expression was encouraged in the illuminations. As noted by Christine Geisler Andrews, the artists “reinvented the compositions and re-interpreted the subjects,” striving to “maintain harmony among the miniatures in a given manuscript.” This also applies to the splendid miniatures in this now disassembled, Book of Hours.

The background of the St. Peter miniature features a diapered pattern of blue, red, and gold squares interspersed with small white flecks. To create a sense of depth, two elegant trees with umbrella-shaped canopies frame St. Peter, seated on a lush carpet of pale green grass. This grass is adorned with delicate flowers and taller blades that gradually darken towards the horizon line, seamlessly blending into the verdant landscape surrounding him.

Diapered patterned backgrounds, grass, blossoming flowers, and framing trees are recurring motifs in late 14th-century and early 15th-century miniatures. Specialist artists likely crafted these elements, while the figures and architectural details were entrusted to master artists. Such picturesque compositions can be observed in commissioned works, such as British Library Harley MS 4431, commissioned by Queen Isabella of France, the wife of King Charles VI and Bodleian Library MS. Douce 144 was likely commissioned for the Dauphin Louis de Guyenne, who would later become King Louis XI of France (see figs. 11 and 12).

Fig. 11 A Collection of Christine de Pizan’s Middle French works, including poetry, letters, and prose, Epistre Otha, 1414, Paris, British Library, Harley MS 4431, fol. 119r, detail.

Fig. 12 Saint Peter with the Key, Suffrages, 1407, Paris, Bodleian Library MS. Douce 144, fol. 130r, detail.

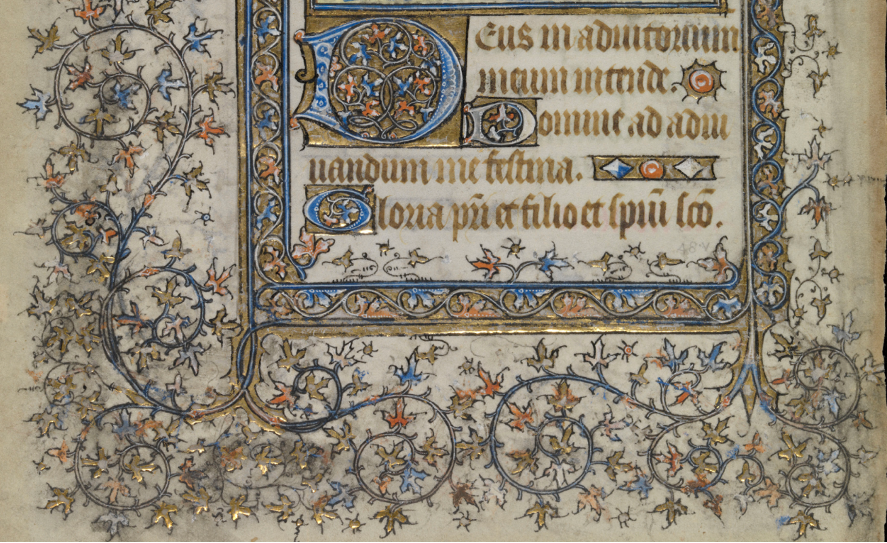

The Significance of Script and Borders

The secondary decoration of St. Peter’s leaf shares many stylistic characteristics with the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry. Both manuscripts demonstrate a consistent decorative vocabulary and treatment of individual elements, including elaborate ivy leaf borders and thick U-shaped frames that elegantly enclose the miniatures (see figs. 13 and 14).

Fig. 13 Mazarine Master, Presentation in the Temple, Hours of the Virgin, 1408, Paris, Chester Beatty Library, WMS 103, fol. 48v. detail.

Fig. 14 Limbourg Brothers, The Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1405-1408, Paris, “The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry”, The Cloisters Collection 1954, Metropolitan Art Museum, folio 52r, detail.

As noted by James D. Farquhar, from the top, bottom and middle sections of the u-shaped staffs sprout multi-coloured stemmed tendrils of cusped red, blue and gold ivy leaves that “gracefully arch into the margin and then double back into a tight loop at the end of the border space like an elegant, attenuated S.” A few ivy leaves also invade the lower horizontal bar of the U-shaped staffs on both text and miniature leaves. There are also interspersed between the ivy leaves, spiked berries and shapes resembling little flying comets with squiggly lines.

Major sections and subsections of the text begin with decorated initials set within squares of burnished gold outlined in black. The squares feature alternating blue and pale pink letters accentuated with white lines and progressively smaller circles. The initials are bordered by red and blue ivy leaves, which are detailed with white tips. Major initials extend across two lines of text, while minor initials are within a single line. To achieve a justified right alignment, rectangular line fillers are used at the end of lines where space permits.

This Book of Hours is remarkable for its dated colophon, carefully executed script with minimal scribal errors, and consistent secondary decoration, as well as for its exquisite miniatures. Equally significant is the rich narrative that has developed through various collectors’ hands, enhancing each leaf’s value and allure. Furthermore, it serves as a testament to the vibrant artistic community of Paris, where the same skilled scribes and artists who crafted illuminated texts for the most exalted aristocrats also catered to the needs of lesser-known noble patrons.

The Book of Hours has faced numerous challenges throughout its history. Created in the heart of Paris during a catastrophic flood that swept away bridges, it was subsequently stored in tin boxes that floated in water for three days. Additionally, it was disassembled by Beatty, who failed to recognise the manuscript’s significance as a reference point for dating other manuscripts. Despite these trials, this manuscript’s leaves and accompanying stories have remarkably persevered.

The surviving leaf with the magnificent depiction of Saint Peter preserves a part of this books’ tumultous history.